Why does India have MRP?

Uncover why India has a unique pricing system for packaged products and how it impacts consumers and businesses.

Go to any store in India, pick up a pack of biscuits and you’ll see a 3-letter acronym stamped somewhere at the back - MRP; the Maximum Retail Price.

But go to the US or Europe and you won’t see that anywhere.

Why not? Let’s dive in.

So, how does a manufacturer really decide the price of its product? Say a biscuit.

They’re probably going to start with how it takes to make the biscuit — the cocoa, the flour, the sugar, then the labour, the packaging, and then a profit margin on top of it. Often, they’ll have to consider the cut for the wholesaler who decides to stock the product and increase the price further. But they also have to consider how much their target customer can pay for it. Oh, and include any local taxes in this process too. And when they put this together, they arrive at a price.

Now the point of telling you this is to say that the government really has no say in how products are priced. Brands don’t really have to give a justification for it. They can tally up some numbers and say, “Look, this is our final price.”

So when you see the acronym MRP, that’s not really the government laying its foot down and saying that there’s a maximum price that someone can charge on the biscuit.

Rather, the concept of MRP as it exists today was originally meant to curb the enthusiasm of retailers. Because back in the day, many manufacturers would print “Retail Price *Local taxes extra” on the back of any packaged product. And then, retailers ended up charging more than what the local taxes actually were. After all, the common man wouldn’t really be aware of the myriad number of taxes, right? So it was an outright loot of the customer

While the image of this old vinyl record by Shakti Films isn’t a case of such loot, you can clearly see the decades old sticker which has ‘Local Taxes Extra’ clearly spelt out.

When the government noticed what was happening, it stepped in. In 1990, it amended the Standards of Weights and Measures Act (Packaged Commodities’ Rules) that was formulated in 1976 and mandated that the final sticker price printed on the package should be inclusive of all taxes.

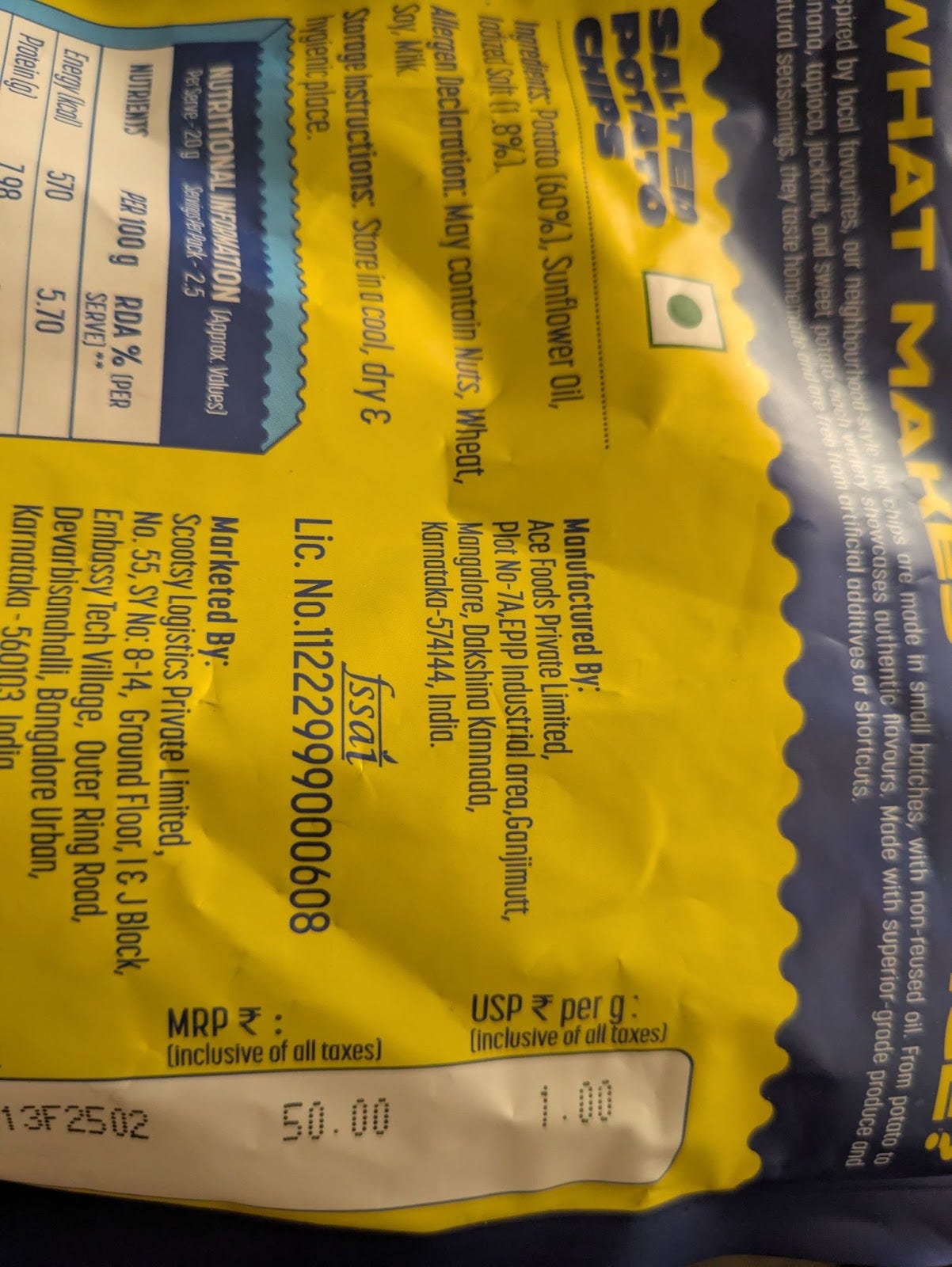

This image of a pack of chips is how the MRP looks today.

You could argue that it was much needed at the time. Access to information was scarce. People couldn’t just hop from one store to another just to ensure that no one was fleecing them and was telling them the right place. And there was really no internet or mobile phones to just quickly look up prices either.

At least with the pre-printed, all-inclusive MRP, customers knew exactly how much they’d pay at the cash counter. No nasty surprises.

Sounds perfect, right?

Or is it?

Because the big argument against MRP is that it flouts the very foundation of free market economic principles.

Hear me out…

When manufacturers decide the MRP, it’s a ceiling on the profits for retailers. And while that may not be a bad thing at first, imagine a couple of these scenarios.

Imagine you make cookies. Really good ones. And then you package it and distribute it to other ‘cookie’ only shops. And you decide that all shops must sell your cookies for a maximum of Rs 100. No more. You print an MRP of Rs 100 on every cookie tin.

Now you have two shops who decide to sell your cookies. One shop is in the city centre. It pays high rents. High costs for labour too because the cost of living is higher.

The other shop is a little out of the way. The rent is dirt cheap and labour and every other cost needed to run the show is just cheaper. Naturally, these folks make higher margins.

Finally, the shop in the city gives up because its wafer-thin margins are just not worth it. They can’t increase the prices either because you’ve printed an MRP on every tin. They shut down. And people in that particular neighborhood in the city can’t get your cookies anymore.

The shop on the outskirts continues to run.

And that’s how the MRP takes away the agency of retailers to charge for premiumness. It doesn’t matter if they’ve done up the store for a better customer experience. It doesn’t matter that they’re in a central location. They can’t charge more and recoup their costs. They’re stuck charging the same price as everyone else.

That sounds quite anti-competitive, no?

This even creates an averaging problem with some regions potentially overpaying. If a single MRP must apply across bustling urban centers to remote villages with significantly higher transportation costs, it can lead to inherent inefficiencies. For instance, for a manufacturer or wholesaler, transporting goods to a Himalayan tea-shop, incurs far greater costs than delivering to a retailer just 10 feet from the factory, yet the MRP must remain the same. People will pay the same irrespective of the location.

Or put another way, someone living in an easy to access location sort of subsidizes the price paid by someone in a remote region.

And while you could argue in support of that too, it does mean pricing inefficiencies remain when you’re attempting a ‘One Nation, One Price’ sort of policy with MRP.

So, is there a better alternative, you ask?

Okay, here’s what happens in most parts of the world including the US and Europe– there’s something called a Manufacturer Suggested Retail Price (MSRP). And just like the name says, it’s simply the price at which a manufacturer suggests that retailers sell their product. It’s a guideline and not an obligation.

This means that retailers can set their own prices – above or below this MSRP — based on their individual costs to run a business. Competition around them will take care of the rest and ensure that things don’t go out of whack.

They believe that it's free market principles, for the win.

So, is it time India gets rid of MRP and gives the free market a chance?

I don’t know about that.

Because even the MSRP is vulnerable to problems. It has an implicit reliance on perfectly competitive markets and fully informed consumers who know when they’re being fleeced or not. But in reality, market imperfections are many and even limited competition for some products could give free rein to the retailers. Or even during times of high demand or scarcity, retailers could resort to price gouging without a second thought.

At least we know that won’t happen with the MRP in place. It’s a safeguard against the worst circumstances. And you also know that whether you’re on the fringes of a forest in Kerala, the foothills of the Himalayas, or the centre of Bengaluru city, if you want a bottle of water you know you’ll pay Rs 10. The MRP. Demand and supply be damned.

So it’s tricky.

But what I can say is that we’ve been conditioned just like Pavlov’s dog. We see the MRP and believe automatically that’s what we must pay. Even though we have no clue how the manufacturer has set the MRP. Whether it’s fair or whether it’s inflated just because they can do it without anyone asking questions.

And maybe that is one thing that needs to change. Maybe India should ask manufacturers to link the MRP to their actual costs – and prove that they’ve done it in a reasonable manner. Maybe that’s what we truly need.

Did you know?

In 2017, international brands such as IKEA, H&M, and Decathlon wanted India to exempt them from MRP. They said that right from producing the product to selling them, it was all in their hands — they were ‘single-brand’ outlets — so price manipulation wouldn’t happen. And the government then exempted them from printing the MRP of every product and instead asked them to comply with a few other rules such as displaying the prices of each product on the shelf.

(Note: There’s not much information on how this has progressed though.)

This Newsletter is written by Nithin Sasikumar.

Do read "What’s your mental accounting with money?" newsletter on our Second Order by Zerodha Varsity.

For any feedback or topic suggestions, write to us at varsity@zerodha.com.

Even though law requires retailers to sell at MRP but the actual price we consumer pay vary across India. MRP is a benchmark against which we can judge whether we've been charged excessively or reasonably. Take the example of Himalayas if you go for treaking to Kedarnath they'll charge from 20 to 100 for a water bottle depending on the heights. Similarly if you go to Bihar generally shopkeeper will charge rs 5 extra for a cold drink bottles. And those with the means deals Directly with manufacturers to inflate the MRP on the bottles, like airport or on expressway (Agra-Lucknow).

Something dynamic with MRP ? as manufactures know where the product is getting delivered so based on that they can make it dynamic for local and for regional profit ?